The morning routine shifts when your office becomes your bedroom. Your alarm goes off at 8:55 AM - why commute early when you're already home - and you shuffle to your desk in the same clothes you wore yesterday. By lunchtime, you've exchanged maybe three sentences with a Slack bot. The refrigerator becomes your only real companion, and by evening, you realize you haven't heard your own voice speak out loud in over twenty-four hours.

This quiet existence slowly reshapes how you interact with the world, creating invisible walls that feel impossibly thick to climb. The worst part isn't the lack of movement or the blur between work and leisure. The worst part arrives gradually, without fanfare, when you notice that words feel foreign on your tongue and other people's laughter sounds almost jarring to your ears.

Your brain has rewired itself for solitude, and that wiring runs deep - so deep that the thought of small talk at a grocery store suddenly feels like climbing Everest in flip-flops. The depressing reality of remote work isn't that it lacks structure; it's that isolation becomes so comfortable you stop noticing you're drowning in it. Nobody warns you that comfort and suffocation can feel remarkably similar when you're living through them.

The Atrophy of Voice and Speech

Your vocal cords remember how to form words, technically speaking. Your mouth knows the mechanics of conversation, the rise and fall of intonation, the split-second timing required to interrupt politely or laugh at the right moment. After months of typing responses to colleagues and recording async video updates where you can retake seventeen times before sending, your actual speaking voice becomes foreign territory. The muscle of conversation - and it is very much a muscle - weakens from disuse, and you start to feel self-conscious about how rusty you've become.

Talking to yourself doesn't count, even though many remote workers do exactly that. Your internal monologue runs perfectly smooth because there's no risk, no judgment, no awkward pauses to navigate. But real conversation with real humans involves vulnerability, the terror of misspeaking, the challenge of reading facial expressions through a screen where you're only seeing someone's eyes and forehead. These skills deteriorate faster than you'd think when your primary communication method involves typing at a pace that lets you correct every thought before hitting send.

The fear of sounding incompetent becomes paralyzing over time. What used to be casual banter now requires mental preparation, like you're about to perform on stage. Your confidence erodes with each month you spend primarily communicating through text, and the thought of phoning someone to catch up sends a spike of anxiety through your chest.

Speaking at the coffee shop

That barista asks how your day is going, and your brain freezes like you've been asked to defend a dissertation. The words that should flow automatically instead come out stilted, overly formal, or you just grunt something noncommittal. Three months ago, you would've chatted easily about the new drink menu or the unusual weather; now you hand over cash and avoid eye contact.

- Your voice sounds strange to yourself, almost like you're performing a character rather than simply existing in conversation

- The depth of the decline becomes visible in these tiny, ordinary moments that used to require zero mental energy

- You start making excuses to order online or use the drive-through to avoid any verbal interaction whatsoever

- The realization hits that you've become someone who dreads a thirty-second exchange with a stranger

Video calls without the camera

When your camera is off during Zoom meetings, something shifts in your internal state. Conversations that require you to perform engagement feel so depleting that you've started finding excuses to turn your camera off - technical difficulties, poor lighting, a full calendar of back-to-back meetings. Your colleagues no longer see you nod; they only hear a voice emanating from a dark rectangle.

- Over time, your ability to participate in group conversations diminishes because you're not reinforcing those neural pathways that activate during face-to-face interaction

- Your presence becomes so minimal that colleagues stop expecting you to contribute, and you stop trying to

- You notice you speak less frequently on calls when your camera is off compared to when it's on

- The lack of visual feedback means you're speaking into a void, which creates the disorienting feeling that nobody's really listening anyway

Forgotten About Being Around Others

Sitting in a room full of people used to feel natural, even if you're introverted. Now it feels like anthropology - observing a species you used to belong to but no longer quite fit within. The small talk that once came automatically now requires an internal script you have to mentally recite. Laughter from coworkers sounds almost alien, as if they're performing for an audience you can't quite see.

The sensory overload of an office environment - the ambient noise, the random conversations, the smell of coffee and printer toner - hits different now that you've grown accustomed to the silence of your home. Your nervous system has recalibrated to expect quiet, which means that ordinary office bustle feels grating and overwhelming rather than stimulating. The worst part isn't that you dislike people; it's that you've forgotten how to simply be near them without internal tension.

Your default setting has become solitude, and socializing now requires effort that feels disproportionate to the reward. You find yourself checking the clock during lunch with friends, calculating how soon you can justify leaving, feeling that familiar anxiety creeping in. The realization that you're actually tired by human interaction - something that never bothered you before - sits uncomfortably in your chest.

Lunch with an old friend

You meet someone at a restaurant, and the first ten minutes feel stiff and formal. Conversation starts and stops awkwardly; gaps in dialogue feel heavy instead of comfortable. The friend keeps asking questions, clearly trying to understand what you've been up to these past months, but you find yourself giving one-word answers or deflecting with questions back to them.

- After an hour, you notice they've talked about themselves more than usual

- You seem slightly withdrawn or confused by your emotional distance

- Driving home, you realize you actually missed them, but something in your presentation made that impossibly difficult to communicate

- The guilt about being distant compounds with exhaustion, leaving you drained for the rest of the evening

What Do You Advocate?

Running into someone at the grocery store

The person recognizes you from before and stops to chat. Small talk about produce and weather should be effortless, but instead you stand there like you're translating from another language. Your body tenses immediately because this conversation was unscheduled and unplanned.

- The whole interaction lasts maybe three minutes, but it exhausts you far more than it should

- On the drive home, you replay the conversation obsessively, analyzing whether you seemed cold or unfriendly

- You hate how much the encounter drained your mental resources for such a brief exchange

- The anxiety lingers for hours after, making you second-guess whether you should've been friendlier or more engaged

Self-Involvement, No External Perspectives

Working from home means your perspective calcifies. The algorithms that feed you content know exactly what you like, so they show you more of it - reinforcing your existing beliefs without challenge. Your conversations primarily happen with colleagues who share your professional worldview, or they happen through text where nuance gets flattened. The friction that comes from hearing opposing viewpoints face-to-face, from being forced to defend your position to someone sitting right across from you, completely disappears.

Self-involvement blooms in this environment like mold in humidity. Without external perspectives constantly nudging against your worldview, you become increasingly focused on your own experience, your own comfort, your own preferences. This isn't malice or intentional selfishness; it's the natural outcome of a life lived without enough friction from other human perspectives. The coffee shop plays music you don't like - that's annoying, why aren't they catering to your taste? A friend suggests a restaurant you're not familiar with - that seems risky, why not just go somewhere you already know?

The tragic part is that you don't realize how narrow your world has become until someone challenges you and you find yourself defending positions you haven't actually thought through. Your thoughts develop in isolation, growing more rigid and narrow, and you mistake that rigidity for conviction. The person you've become is gradually unrecognizable to the person you were before the isolation set in.

Creating your perfect remote setup

That chair, that desk, that lighting, that background for video calls - all of it becomes optimized solely for your comfort and preferences. You spend three weeks researching the perfect monitor setup because nobody is around to tell you to stop obsessing about something so minute. Your home office becomes less about functional productivity and more about a shrine to your specific needs and tastes.

- If something isn't precisely how you like it, you change it immediately because no one else's preferences enter into the decision-making process

- The space becomes so perfectly tailored to your idiosyncrasies that it feels jarring to work from anywhere else

- You find yourself bringing a special chair or monitor to coffee shops because the standard setup there feels wrong

- This further cements your attachment to your isolated setup, making you less willing to work in shared spaces

Deciding what to eat every day

Without colleagues suggesting lunch spots or the casual social contract of group eating, your dietary choices become entirely self-directed based on what sounds good in that exact moment. Three months in, you realize you've eaten basically the same five meals on rotation because they require minimal decision-making. You've never tried the new restaurant because you don't know what they serve well, and uncertainty feels worse than boredom.

- The decisions that used to get made through social negotiation now get made by a narrowing list of what feels safe and familiar

- Your world of culinary experience shrinks without you noticing, and you become someone who eats the same thing obsessively

- Trying something new requires effort that your isolated brain interprets as a threat rather than an opportunity

- Over time, you realize you've become boring even to yourself, stuck in the same routines with the same foods

The Invisibility That Feels Like Freedom

At first, invisibility feels like a gift. Nobody witnesses your 10 AM coffee break or the fact that you've been wearing the same hoodie for four days straight. No one tracks how many times you've browsed social media instead of working. The lack of observation feels liberating - nobody's judging your appearance, your body language, your productivity on a particular afternoon. This freedom becomes addictive, perhaps even more so than nicotine or caffeine.

But invisibility corrodes something essential in the human psyche. Humans need to be seen and acknowledged by other humans to maintain a sense of reality and validity. When months pass without anyone actually perceiving you - really seeing you, not just reading your words on a screen - something starts to hollow out internally. You become increasingly unreal to yourself, like a character in a book nobody is reading. The depression that emerges from this invisibility isn't sadness; it's a peculiar form of existential doubt, a creeping suspicion that you might not actually exist outside the boundaries of your apartment.

The strange paradox is that freedom from judgment turns into a prison of irrelevance. You're free from observation, but that freedom comes at the cost of mattering to anyone. Your work gets done, your meetings happen, your salary deposits, but nowhere in that process do you feel actually necessary. The invisibility that once felt like liberation now feels like erasure.

The unmuted video call presence

During a meeting, your camera is on but you don't speak for forty-five minutes. People refer to you occasionally - "What do you think?" - and you give a two-sentence response before falling back into silence. As the meeting ends, nobody asks if you're doing okay or makes you feel like your absence of participation was a problem. In fact, they probably didn't even notice.

- Nobody needs you to contribute; the work gets done without your voice or ideas mattering much

- That realization settles into your stomach uncomfortably as you close the meeting feeling more invisible than before

- Over time, you start thinking there's no point in showing up at all if you're this irrelevant

- The meetings you used to find tedious now feel like your only connection to others, yet they leave you feeling more isolated

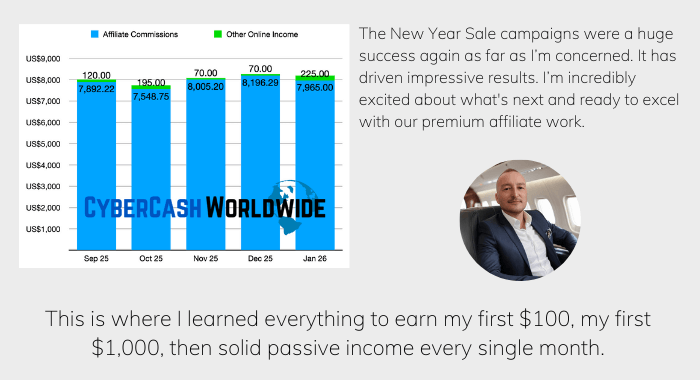

How I "Finally" Make Over $7,000 Monthly Income

"The most valuable thing I've ever done!"

The lack of witness to small victories

You solve a complex problem or finish a difficult project, and there's nobody around to acknowledge it. In an office, someone would notice - you might grab a colleague and walk them through your thinking, or someone would overhear and congratulate you casually. Now you stare at your finished work, feel a moment of satisfaction, and then what? Slack it to your manager and get a thumbs-up emoji?

- The accomplishment happens in a void, celebrated only by yourself

- Over months, these small victories start to feel less meaningful because validation exists only in your own assessment

- The external witness that makes achievements feel real disappears entirely from your work life

- Your sense of professional growth stagnates because there's nobody to reflect back to you that you're actually getting better at your job

The Spiral Downward

One depressing consequence compounds the next with clockwork precision. Your voice atrophies, so speaking feels harder, so you avoid it, so it atrophies further. You become invisible, so you feel less real, so you withdraw more, so people notice you less. Your worldview narrows because you're around fewer perspectives, so you become less interesting at social gatherings, so you get invited fewer places, so your worldview narrows further. The negative feedback loop becomes a tornado that sucks you deeper into isolation with each rotation.

The worst part isn't that this happens - the worst part is that it happens slowly enough that you adjust to each new level of dysfunction as if it were normal. The bar for human contact keeps lowering. Three months without seeing anyone in person starts to feel acceptable. A phone call with a family member gets crossed off your mental to-do list as "sufficient human interaction for the week." Speaking to someone face-to-face starts triggering anxiety that rivals public speaking phobias. Your internal standards for what constitutes a healthy social life have shifted so dramatically that you've lost the ability to recognize how far you've drifted.

The real horror is that each adaptation feels reasonable in the moment. Skipping one social event doesn't feel catastrophic - it's just practical. Not calling your parents for a month isn't abandonment; it's just being busy. Eating lunch alone at your desk instead of going out doesn't feel sad; it's just efficient. But these tiny, reasonable adjustments accumulate until you're living a life so isolated that depression becomes the obvious and inevitable result.

The month everything gets darker

Month four or five of full remote work arrives, and suddenly you notice that calling a friend feels like an obligation rather than a pleasure. You go to social events but spend half the time thinking about your work deadline, meaning part of your attention exists elsewhere. Conversations feel shallow and effortful in ways they never used to. You start canceling plans with increasing frequency, initially telling yourself it's because you're busy - and maybe that's true - but underneath runs a current of "I don't have the energy to pretend to be normal around other people."

- The depression that was lurking quietly suddenly takes center stage

- You struggle to identify exactly when things got this bad, because the decline was so gradual

- Looking back, you can see the markers you missed - the declining frequency of social contact, the increasing difficulty of conversation

- The present moment feels hopeless because you can't pinpoint where the trajectory changed

Breaking the Isolation Without Losing Your Mind

The solution isn't to abandon remote work entirely or shame yourself for enjoying the flexibility it offers. The solution involves small, deliberate actions that reintroduce elements of human interaction and external perspective without overwhelming your nervous system. These actions feel artificial at first because they are artificial - you're consciously overriding the comfort of your current routine. That discomfort is actually the point; it signals that you're interrupting patterns that have calcified into dysfunction.

Scheduling in-person meetings that have no particular agenda can feel strange, but the structure forces you to remain present and engaged. Changing your work location every few days - even just to a coffee shop - reintroduces ambient human presence and the slight friction of not being in your perfect setup. Speaking your thoughts aloud, even into a voice memo, helps exercise those vocal pathways and reminds you that words sound different inside your head versus in the actual world. The mechanisms of recovery are less about dramatic life changes and more about consistent, small interventions that gradually restore the connections you've let atrophy.

The deeper truth beneath all this darkness is that human beings evolved to exist within social structures, and remote work can sever those connections in ways that feel almost painless until suddenly they don't. Your isolation isn't a personal failing or a character flaw; it's a predictable outcome of an environment designed for maximum efficiency and minimum social friction. Acknowledging that the current setup has created depression and disconnection isn't weakness - it's the first step toward actually changing course.

Your recovery won't look like what recovery looks like for someone else, because your particular version of isolation carries its own specific contours. But recovery remains possible, and it starts the moment you stop accepting silence as normal and begin reaching out, speaking up, and demanding that other human voices remain part of your daily existence. The alternative - a life lived entirely in your own head, circling the same thoughts and preferences until you can no longer distinguish between comfort and stagnation - isn't actually freedom. It's a different kind of prison, one you built for yourself without quite realizing the walls were closing in.